Reconciling Gratitude and the Power of Creative Discontent

Many extended families will gather this Thanksgiving in the biggest home of the brood; take their places under that roof, around long tables; have each member specify some small thing that they are “thankful for”; and then gorge themselves on turkey, cranberry salad, and other standards. After, they might loll around in food comas in front of the television, play Yahtzee, catch up, horse around outside, or go see a movie.

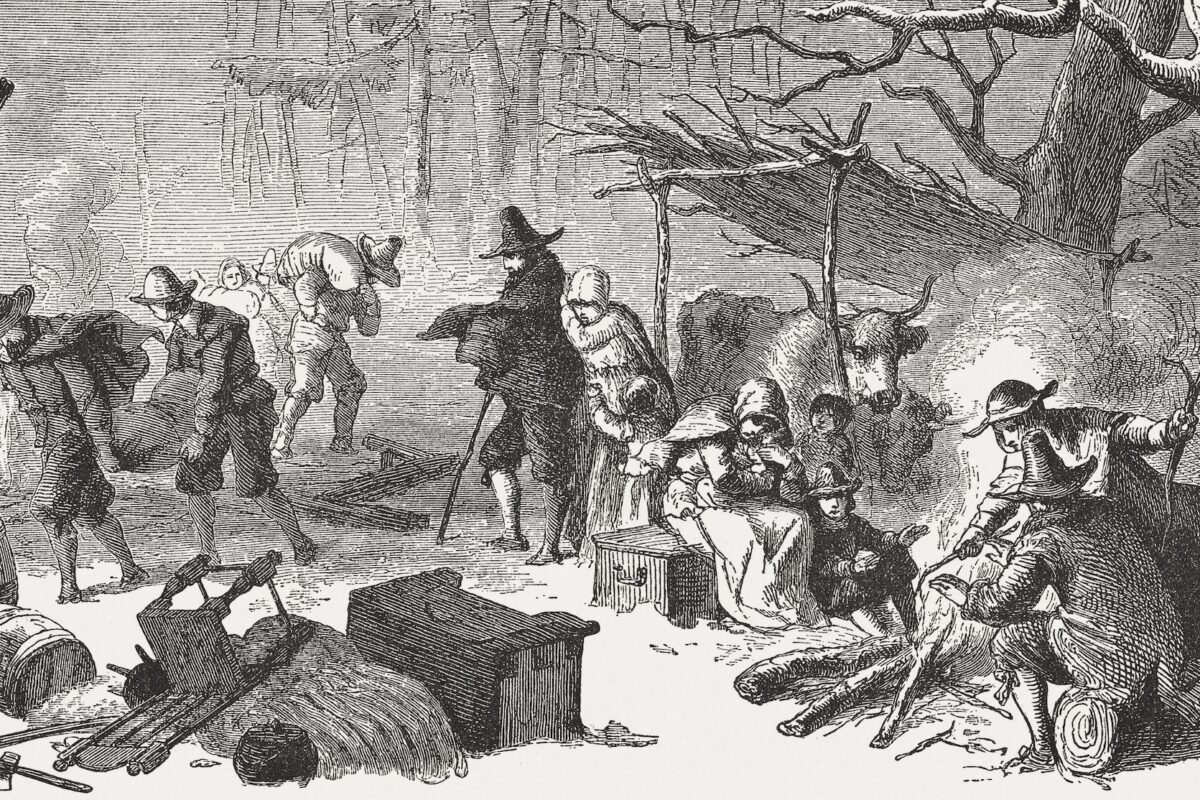

It’s hard for us to understand today just how precarious the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth Plantation was. So try this: Take the above picture and subtract the roof, the table, the cranberry salad, even the turkey. Also, imagine that over the last year, half of your family had died. Now: What are you thankful for?

In late 1621, the Pilgrims were thankful that they just might make it through another winter. Their first one in the New World had been a deadly disaster. Their voyage was delayed because one of their ships sprung several leaks, likely due to sabotage. Then, instead of the moderate weather they expected in America, they were hammered by a harsh and relentless New England winter.

The ship that finally ferried them across the Atlantic, the Mayflower, returned to London far later than planned with nothing to show for the trouble. The ship was supposed to return with produce to pay back their creditors, but the new colonists had nothing to spare. The Mayflower stayed anchored throughout the winter out of necessity. The Pilgrims used it for shelter because they had precious little of that to give them a reprieve from the snow, the winds, and the cold.

They had some shelter almost a year later—but not much. We see this reflected in many Thanksgiving paintings in which Pilgrims eat outdoors at a long table. But the truth is they probably didn’t even have that much.

“Tables and even chairs were scarce…knives were rare…and forks were nonexistent” at Plymouth Plantation, explains Robert Tracy McKenzie in the book The First Thanksgiving. When we think of that first Thanksgiving meal, he says, “we should picture an outdoor feast in which almost everyone was sitting on the ground and eating with their hands.”

It was indeed a feast—one that featured:

- fish, shellfish, and possibly eel

- birds, though probably not turkeys

- venison supplied by their guests, the Wampanoag Indians

- maize, grown from a native stash the Pilgrims found and, well, let’s go with borrowed

- plus various herbs and root vegetables

But that had to taste bittersweet to many of these new settlers. The deaths had leveled off but the toll was high: 102 people had set sail; only 51 or 52 remained that first Thanksgiving. “As many as two or three people died each day during the first two months on land,” explains the Plantation’s official website.

That attrition left many husbands wifeless, many children parentless, and was especially tough on both the very old and the very young. Only three people over 40 were left standing. Two babies had been born en route to and in this new world; one of them had already died.

I bring up this material gulf between the Pilgrims and Americans in the present not to shame us in our food comas— though really, turkey? We can do better! Bring back eel!—but rather to show how things have progressed. By the standards of history and in the eyes of most of the rest of the world, Americans are incredibly wealthy. We have shelter, heating, food, non-leaky ships, and kitchen utensils in abundance. And we have a pretty good handle on disease. Our lives are long and we have made horrific things such as infant mortality rare.

The great thing about the American experiment that the Pilgrims accidentally helped launch is that even those successes are not enough. We ought to be thankful for what we have, and the example of the Pilgrims helped to cement that in our national DNA. But another strand of that DNA, which the Pilgrims also had something to do with, tells us that we can go further, take chances, do something that will leave a mark that folks 400 years from now will still be talking about.

Gratitude and creative discontent are not mutually exclusive. These are the twin lessons I leave leaders to chew on this Thanksgiving.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.