Why We Shouldn't Paper Over This Success Story

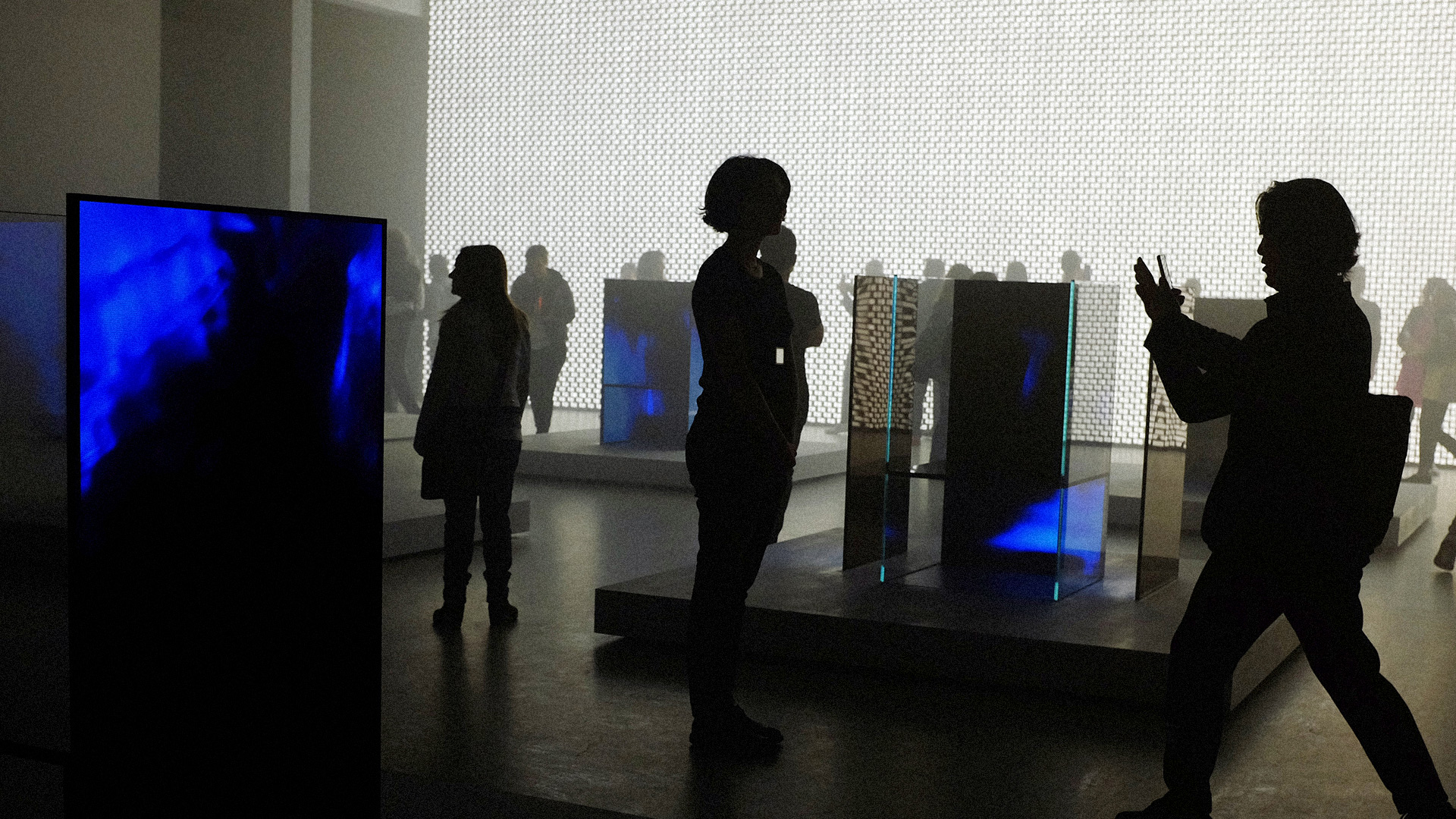

If you ever attend Milan’s Design Week—a sweeping furniture fair, art festival, and Prosecco-soaked party that takes over Italy’s financial capital each April—you will need several essentials to fit in with the global trendsetters in attendance.

First, your glasses. This is a design crowd, so the options are polarized into two camps: ultraminimal frameless spheres that hover over your face, and inch-thick acetate beasts. Next, your clothes. Leave ankle-snapping heels and impossible dresses to the fools at Fashion Week; the name of the game here is the ideal mix of form with function, such as a limited-edition pair of Converse clad in sharkskin. Also scarves. You can never wear too big a scarf at Design Week, even if a sudden heat wave descends on the city.

Finally, there’s your kit. If you carry a bag, it needs to be small, streamlined, and slung over the shoulder. In one hand, firmly grasp the latest iPhone, which you’ll use to take photos of new chairs and kitchen tile installations, stay in touch with colleagues, and navigate your way between parties and events all over Milan.

In hand number two

In the other hand, you will carry a black Moleskine notebook. Perhaps you will bring the same, lovingly worn Moleskine back to Milan year after year, or maybe you will unwrap a fresh one at the start of every Design Week. You will jot quick notes and sketches in it as you tour showrooms and exhibits, and at the end of each long day, you will open it on a café table, order a cold Peroni and a plate of mortadella, put pen to paper, and digest all the exhibits, products, and far-reaching designs you’ve seen since the morning. You might start by writing lists of words, maybe descriptive adjectives, or a few lines of insights that tease out this notion you have forming about the organic desire for analog experiences in a hyper-digitized age.

After a page or two, you’ll stop, take a sip of your beer, and look around. You’ll draw inspiration from the pale gold of the beer, the beautifully irregular spots of the mortadella, the bleached ceramic plate it sits on . . . and suddenly you’ll be designing your own textile line, filling pages almost as fast as you can turn them, with sketches and words and feverishly added details.

Yes, I am being romantic, and perhaps mortadella isn’t a traditional muse. But this is exactly what I saw at the end of each day during my visit to Milan in the middle of Design Week. Moleskines . . . hundreds of them, thick with the ideas being written and sketched in them by the most talented and driven design minds in the world. Old designers, young designers, European designers, and Asian and Latin-American designers—the Moleskine notebook is their common tool. You certainly do not need to visit Milan to witness this. Just step into any coffee shop, pretty much anywhere in the world, and you will find Moleskine notebooks resting on tables next to lattes and laptops. With their rounded corners, elastic closure, and ivory paper, they are instantly recognizable. Which is why I see them everywhere: in the hands of teachers, on my doctor’s desk, in the bags of computer software programmers.

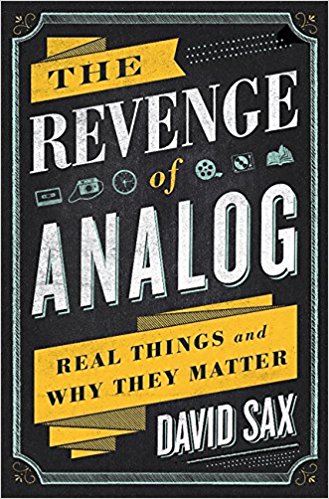

Nearly everyone I interviewed for my book, The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, pulled out a Moleskine notebook at some point, or had one sitting nearby. For a thoroughly analog object, the Moleskine is one of the iconic tools of our digitally-focused century.

Nearly everyone I interviewed for my book, The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter, pulled out a Moleskine notebook at some point, or had one sitting nearby. For a thoroughly analog object, the Moleskine is one of the iconic tools of our digitally-focused century.

I am fascinated by Moleskine for several reasons. Paper was the first analog technology to be seriously challenged by digital. Even before the rise of the personal computer, the term paperless office had emerged as an obsession of the business world by the late 1970s. The promise of a computer reducing the cost, labor, and space associated with printing, storing, and organizing so much physical information was powerful. Office workers were called “paper pushers” for a reason, and less time pushing paper meant more time, and money, devoted to other work. Although the fully paperless office has yet to come to fruition, certain paper artifacts are now largely digital. E-mail, texts, and PDFs have taken the place of memos, telegrams, and faxes. When I entered university in 1998, I was one of the few students to take class notes on a miniature laptop. Today, screens overlook college lecture halls. Paper hasn’t disappeared, but it is no longer dominant.

Paper is also the oldest analog technology to be seriously challenged by digital. Vinyl records had been around less than forty years when the CD came out, but paper has existed, in one form or another, for thousands of years. It is the backbone of the economic, cultural, scientific, and spiritual core we call civilization. Even the bound notebook, the core technology behind Moleskine’s main product, predates European settlement of the Americas. Our relationship to paper is older, deeper, and more varied than any other analog technology out there. Understanding where paper’s advantages lie, where it has struggled to compete with digital technology, and where it has crafted a new sense of identity is key to understanding how the Revenge of Analog is playing itself out.

Where paper is growing

The revenge of paper shows that analog technology can excel at specific tasks and uses on a very practical level, especially when compared to digital technology. While paper use may have shrunk in certain areas since the introduction of digital communications, in other uses and purposes, paper’s emotional, functional, and economic value has increased. Paper may be used less, but where it is growing, paper is worth more.

From the get-go, Moleskine knew that its notebooks wouldn’t exclusively contain the brilliant creations of the next Picasso. There would be a lot of melodramatic teenaged diaries, half-baked doodles and class notes, and grocery lists. But because they were written in a Moleskine, they would still feel more creative than if they were scribbled on another piece of paper.

“Creativity is a word that’s now completely sold,” Maria Sebregondi, the founder of Moleskine, said, “but the concept behind it is strong and real. People want to be creative and feel creative, even if they are not. Creatives have the ability to create an emotional trigger, and the analog world is the one able to create this emotional attraction and experience.”

This formed an almost tribal identity around the Moleskine notebook and those who used it. The notebook became a symbol of aspirational creativity, a product that not only worked well as a functional tool, but that told a story about you, even if you never wrote on a single page. Like a Patagonia jacket or a Toyota Prius, it projected someone’s values, interests, and dreams, even if those were divorced from the reality of their lives.

This is why Moleskine never needed to advertise, and never does to this day. Each notebook spotted at a coffee shop table, or in the hands of a journalist, was worth more than any billboard or magazine page. “This is a company that went from being a category maker to a category icon,” said Antonio Marazza, general manager at the Milan office of the global branding agency Landor Associates. “The emotional and aspirational capital Moleskine can deliver goes beyond stationery.”

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.