Why Lincoln, Henry, and Sojourner Truth Stood Out

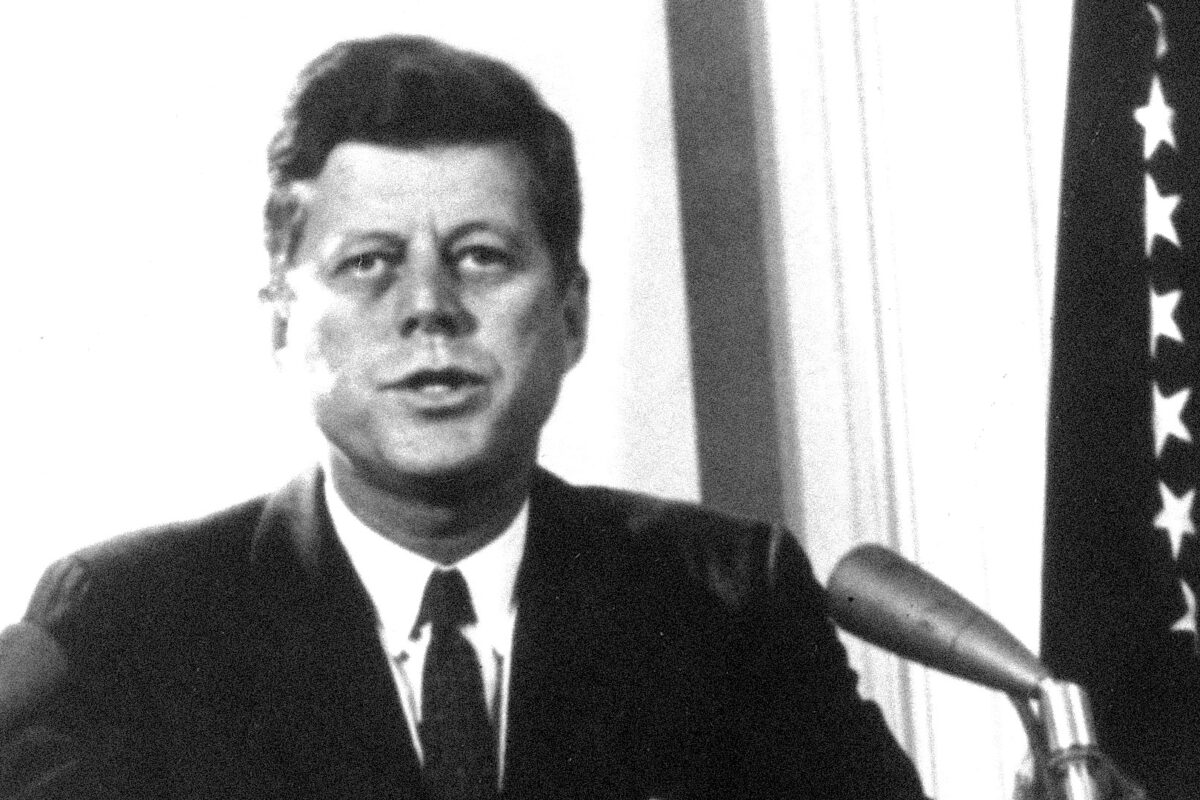

People have delivered countless speeches in history. But even speeches delivered by the most prominent people, on the most auspicious occasions, routinely make little difference. Think of presidential speeches, like inaugural or State of the Union addresses. How many of them had any lasting impact? Just a few, like John F. Kennedy’s 1961 exhortation to “ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.”

What makes great historic orations so powerful? Typically, they combine well-crafted words, clarity of thought, moral passion, and an uncanny sense of historical timing. Many of the greatest speeches of history were not destined to become great. Often the speaker was not the most famous person in the room, or was not giving the keynote address. Sometimes the oration was so unexpected that we don’t even have the text of the original speech. But that combination of apt, passionate words, delivered at the right moment, sometimes changes the course of history.

Three examples will illustrate my point. The first and third of these speeches you probably know; the second speech, you might not.

Liberty or bust

The first speech is Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” oration in 1775 in Virginia, on the eve of the American Revolution. This was the most influential speech in inspiring the war of independence against Britain. Henry was already known as a brilliant, fiery orator in 1775. Some said that he spoke like the revivalists of the Great Awakening, whose meetings he had attended as a boy in the mid-1700s.

The Patriots at the Virginia Convention, meeting at St. John’s Church in Richmond, were divided between those who wanted to keep seeking reconciliation with Britain, and those like Henry who saw war as the inevitable outcome of their struggle over taxes and British power in America. Henry called on his fellow colonists to muster the courage to fight. “I know not what course others may take,” Henry thundered, “but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!” Part of the moral urgency of the short speech came from its repeated invocations of the Bible, especially the prophet Jeremiah. As was Henry’s style, “Liberty or Death” was part sermon, part speech.

“Liberty or Death” was also the most famous oration in American history for which we do not have the original text. Whether Henry failed to write down the speech or did not save a copy, we don’t know. The text we have was patched together forty years later, by an admiring historian. But Americans had already adopted the slogan “Liberty or Death” as a battle cry in 1776. Slaves knew the phrase, too, and made their own use of it. The slave rebel Gabriel in 1800 in Richmond reportedly intended to lead his collaborators marching under a banner reading “Death or Liberty.”

Woman speaks up

The author of our second speech, Sojourner Truth, was herself a former slave in New York. She delivered her 1851 oration “Arn’t I a Woman?” at a women’s rights convention in Akron, Ohio. Even more than Henry’s Liberty or Death speech, “Arn’t I a Woman?” took on a life of its own afterwards, becoming one of the most commonly cited historical addresses by an African American woman. The illiterate Truth (born Isabella Baumfree, but changed her name in 1843) boldly addressed those who said women should have no political rights. “I can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that?” she asked.

Twelve years later, a friend of Truth’s recalled that she also declared, “And arn’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen them most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And arn’t I a woman?” As with Henry’s “Liberty or Death,” we don’t have the original text of Truth’s speech. But she spoke with unprecedented power and passion about the struggles of a woman and a slave in pre-Civil War America.

Forgetting Everett

Finally, there’s Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, given in 1863 at the dedication of the Union cemetery at the Gettysburg battlefield. This has become one of the most famous speeches in American history. It is so brilliantly brief that countless American schoolchildren have memorized it. But Lincoln was not even the featured speaker at Gettysburg that day. That role fell to Edward Everett, a former congressman and Harvard president who was probably the nation’s most celebrated orator in 1863. Everett gave a two-hour long speech which was probably well received at the moment, but which is now almost totally ignored.

No one expected Lincoln’s two-minute remarks to change the meaning of the war and of American history. Before the Gettysburg Address, many white Americans – including northerners – did not wish to extend the blessings of liberty to African Americans. But Lincoln insisted that the Declaration of Independence had founded a nation “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

“Under God,” he proclaimed, America would have “a new birth of freedom.” His audience would have instantly understood what Lincoln meant. Because of the Civil War, America itself could be “born again,” as the Gospel of John puts it, into a new life of freedom: freedom for slaves. Moreover, he believed that the Union army’s victory would ensure that “government of the people, by the people, and for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Unexpected orations

These examples show that the greatest speeches are not always easy to anticipate beforehand. Many critics did not believe that Sojourner Truth, as a black woman, should even be speaking in public in 1851. Lincoln and Henry were far more prominent and accepted figures, of course, but Lincoln was not the main speaker at Gettysburg, and no one bothered to write down and save Henry’s speech. Yet all three, under differing circumstances, combined the right timing, clarity, and moral power to craft history-changing speeches.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.