The Story Behind Winning the Peace Prize

Martin Luther King’s path to the Nobel Peace Prize took him to several countries and included encounters with J. Edgar Hoover, and the founders of the British civil rights movement. But it began with a Quaker in Philadelphia.

Colin W. Bell, a career charitable worker, wrote the first nominating letter that led to King’s award, the second Nobel Prize for Peace awarded to an African-American. (Diplomat Ralph Bunche received the 1950 prize for negotiations in the Arab-Israeli conflict.)

Bell sounds out Nobel

The British-born Bell had done Friends relief work in Asia and managed a medical unit in China during World War II. At the time he nominated the civil rights legend he was executive secretary of the American Friends Service Committee. The Nobel Foundation includes “directors of peace research institutes and foreign policy institutes” as qualified nominators for the Peace Prize.

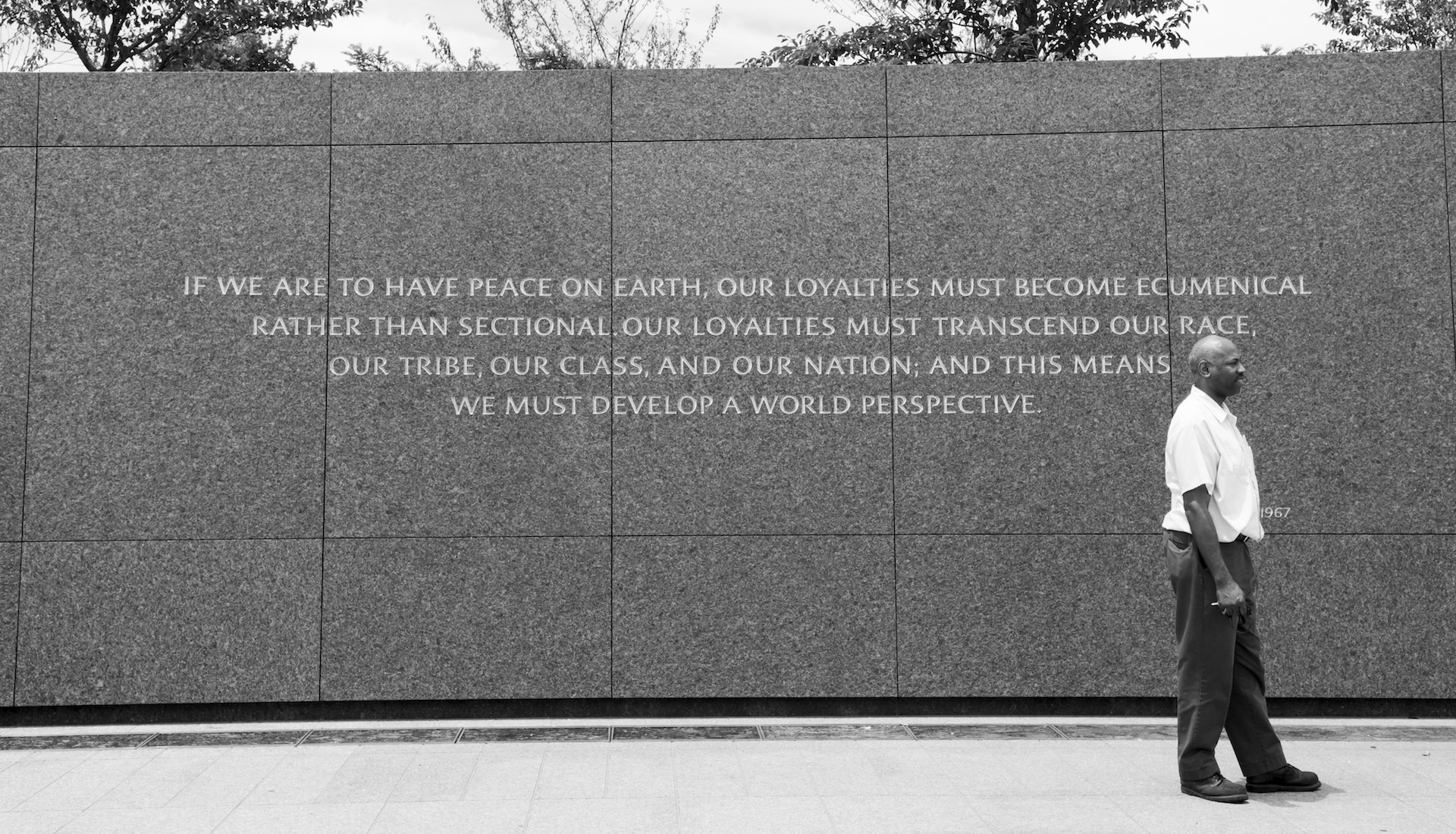

“The Board, in reaching its decision, was conscious of the baleful effect of racial tension upon the organization of peace” Bell wrote. “It felt that the work and witness of Martin Luther King, and the spirit in which he promoted ‘the dignity and worth of the human person,’ were influencing the attitudes of great numbers of men and women throughout the world. Until the attitudes epitomized in the life of Martin Luther King were to spread among individual men the nations could not achieve real peace.

“In this respect Martin Luther King’s influence went far beyond the issue of racial tension, and pointed the way to basic new relationships between men everywhere.”

Red crossed

In its full nomination, the American Friends Service Committee played up the international dimension of King’s movement, emphasizing the risks revealed by the Cuban missile crisis and pointing out the potential that leaders of the anti-colonial movement in Africa might adopt non-violence.

But there was a hitch. The Friends nomination was sent in 1963, and the award that year went to the International Committee for the Red Cross. Nobel nominating rules set a February deadline for submissions, and Bell’s letter reached Oslo after the due date.

At the end of the year, Bell renewed his support for King and asked that the nomination be rolled over for 1964, a request the Nobel Foundation granted. King was one of forty-four nominees that year. Among the others were socialist politician Norman Thomas, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, and the Shah of Iran.

Swedes had a dream, too

Much had happened since King’s first nomination. The August 1963 March on Washington focused international attention on the American civil rights movement, and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech took its place in the catalogue of great rhetoric. King also received an important second nomination, this time in a letter signed by eight members of Sweden’s parliament.

“Because of his strong influence,” the Swedish politicians wrote, “he has managed to get his followers to adhere to the principle of nonviolence. Without King's firm conviction of the rightness and effectiveness of this principle, demonstrations and marches could easily have given way to riot and ended in bloodshed… King has helped establish that not hatred but reconciliation, understanding and respect have become hallmarks for both sides in the fight against racial discrimination.”

The Swedes also pointed up the global dimension of the non-violent civil rights movement. “Dr. Kings' efforts in the United States can be pattern-forming in the struggle for justice and equality elsewhere in the world,” they wrote, “thus contributing to the resolution of separate conflicts with peaceful means.”

Testing the dream

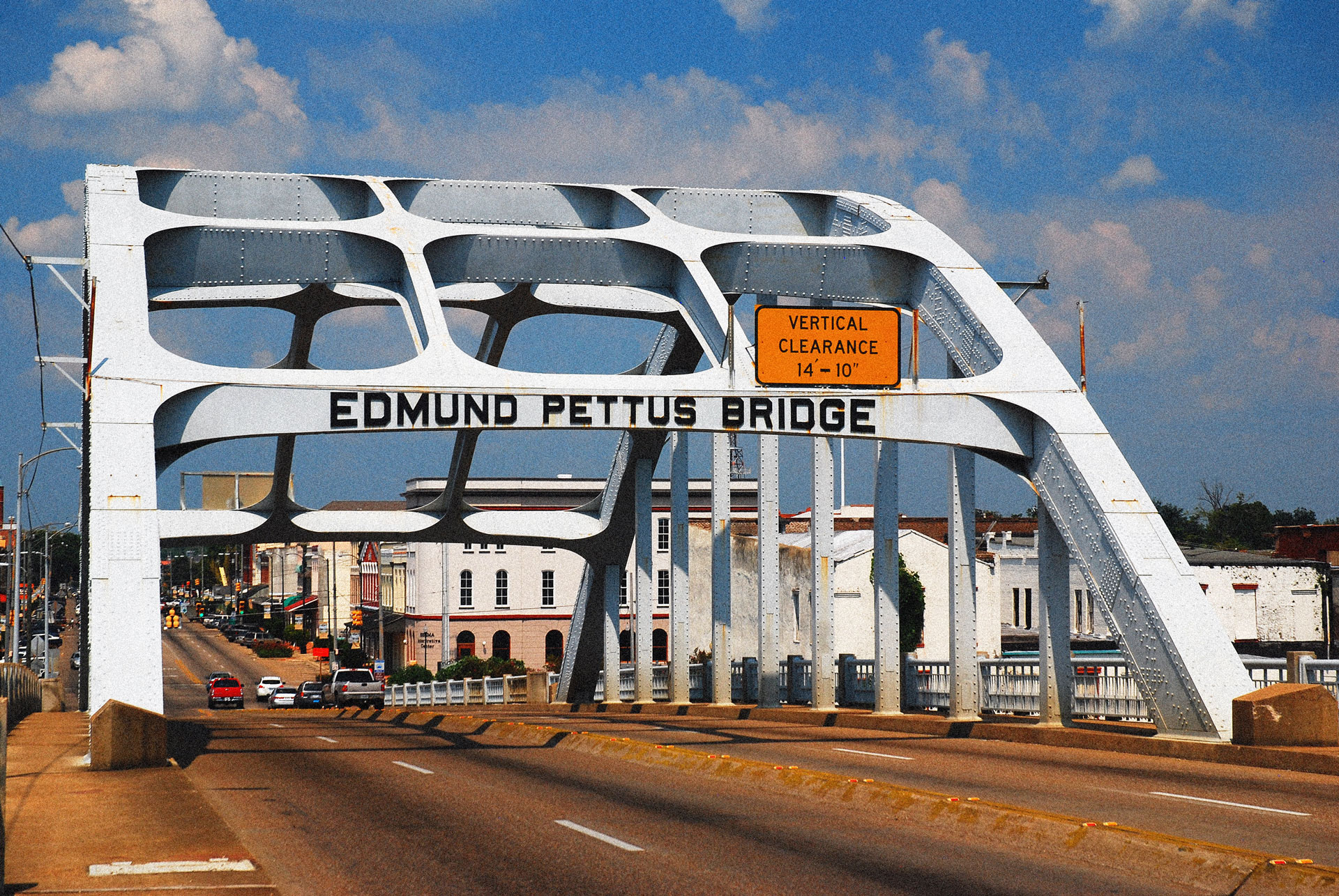

The year 1964 also brought doubts that non-violence would win the day. A riot broke out in Harlem in mid-July, followed a few days later by one in Rochester, New York. North Philadelphia erupted in late August. The unrest in the three cities resulted in five deaths, hundreds of injuries, and more than 2,000 arrests.

The violence led some observers to question the southern, rural King’s ability to speak for urban blacks. “Martin Luther King can’t reach those people,” novelist James Baldwin said. “I think he knows it.”

The October announcement of his prize came at a low point for King. He had checked into an Atlanta infirmary, pleading exhaustion, when his wife Coretta brought the good news. At thirty-five, the reverend was then the youngest person ever to receive the peace prize.

The journey didn’t end there. Prior to leaving the United States, King had a long, confidential meeting with FBI director Hoover, whom he had long criticized over the Bureau’s civil rights record. On the first leg of his trip to Oslo, King stopped in London and spoke at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Malcolm X, King’s ideological opposite in the Civil Rights movement, was in London at the time, and in his public statements King minimized the appeal of militancy and separatism.

“Negroes in the United States are more in line with the philosophy of integration and togetherness, and not in line with racial separation,” he told reporters. King’s most consequential encounter in Blighty was with a small group of local activists at the Hilton, who went on to found the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, Britain’s first modern civil rights organization.

King’s “renewed dedication”

King had fewer than four years to live when he received his Nobel Peace Prize. Bell continued his work for the Friends until the late sixties and died in 1985. In his acceptance speech, King placed his own prize in the context of a mass movement with millions of unknown activists.

“Today I come to Oslo as a trustee, inspired and with renewed dedication to humanity,” King said. “I accept this prize on behalf of all men who love peace and brotherhood. I say I come as a trustee, for in the depths of my heart I am aware that this prize is much more than an honor to me personally.”

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.