A New Guide to Clear Thinking in a Confusing World

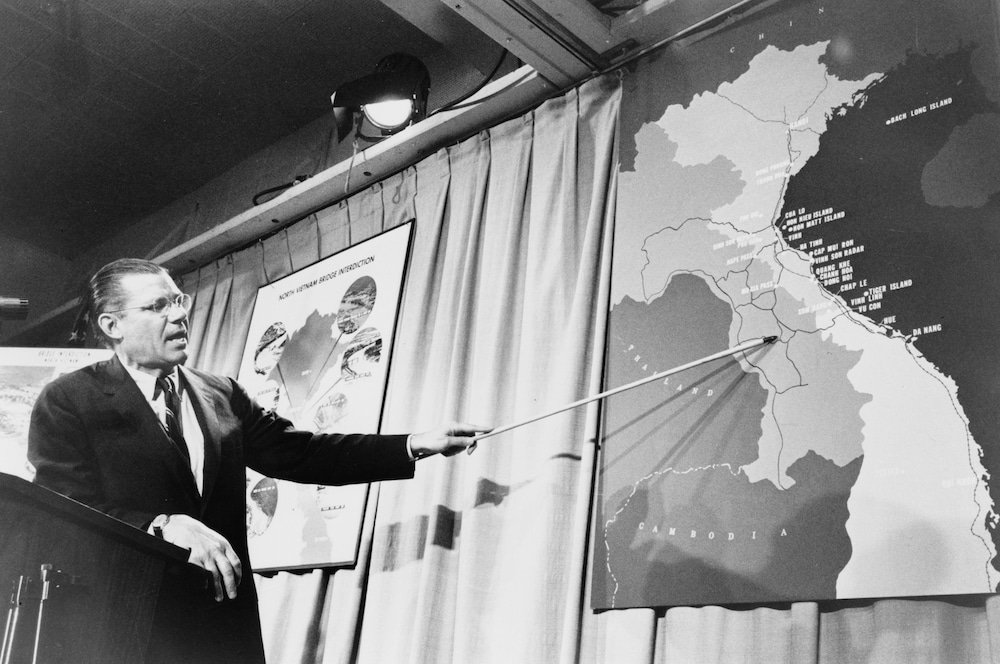

During the early days of the Vietnam War, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara wanted to know if American military efforts in Vietnam were effective. He charted the numbers of weapons lost, enemies killed, and so on. But there was a hole in his thinking.

A critical colleague told McNamara he’d failed to count “the feelings of the Vietnamese people.” It was a fatal miss. While experts in Saigon and Washington insisted America would win the war in no time, it seems clear from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s new documentary that alienating the South Vietnamese spoiled any chance of American victory.

Robert McNamara. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

It’s easy to spot the failures at this distance, but the truth is we’re all prone to similar miscalculations and flawed thinking—usually just less disastrous.

Smart people think, say, and do stupid things all the time. One explanation is that we're sometimes more intelligent than critical. Researchers who’ve studied the discrepancy between intelligent people and stupid decisions note that critical thinkers experience fewer negative events in life, even when compared to highly intelligent people. Why? Their critical lens helps them avoid traps others blindly stumble into.

The good news, the researchers say, is that we can all learn how to think more critically. To do so takes more than just thinking. It requires thinking about our thinking. And for that, there are few guides better than Baylor professor Alan Jacobs’ new book, How to Think.

A Process, Not a Product

We often mistake thought for a product. After all, it’s what our brain produces. But thought is really a process. Since we usually focus on what—and not how—we think, we’re liable to stumble into unseen traps. Thankfully, Jacobs illumines our path.

He starts by explaining most of our thinking isn’t really thinking. It’s more like mental shortcutting. If we had to dissect the world at every turn, we’d never get anywhere. We all develop habits of mind that help us compress and even sidestep most of the thinking we might otherwise have to do (which is good news because we’ve got mortgages to pay). The problem is that some of that shortcutting fails us, and we fall for traps set by our own false assumptions or hasty conclusions.

We cook up some of these shortcuts on our own, but many are given to us by others. Jacobs points out that we never think in a vacuum. “Everything you think is a response to what someone else has thought and said,” he says. But it goes beyond that. Our thinking is heavily influenced by our social circles. “To dwell habitually with people is inevitably to adopt their ways of approaching the world.” If we’re not critical enough in our thinking to recognize how the process works, we default to unhelpful attitudes, ideas, and practices.

Dangerous Myths

During Vietnam, Cold War mythology shortcut critical considerations about Vietnamese reunification and independence. It’s a cautionary tale. If we’re self-unaware, mythologies of all sorts can wreak havoc in our business, politics, relationships, and more. Just look at social media, where a single hashtag can substitute for an entire train of thought—or, more accurately, its absence.

Hashtags exemplify what Jacobs calls “keywords,” by which he means the terms any given community takes for granted. If you’re in the group, you know what they mean (more or less) and use them accordingly. Sometimes these keywords stand for bigger metaphors and full-blown myths. But these keywords can replace actual thinking. They’re like an autopilot system steering us toward some truths, while skirting others. Occasionally, they send us into a ditch.

“We come to rely on keywords, and then metaphors, and then myths,” he says, “and at every stage habits become more deeply ingrained in us, habits that inhibit our ability to think.”

Alan Jacobs. Photo by Holly Fish

The more invested we are in our myths, the less likely we are to change our minds or value those who hold differing views. For leaders, the stakes are higher, thanks to the power differential inherent in their positions. Self-unaware leaders are likely to devalue the ideas of their own team members.

Avoiding the Traps

Once we see how and why we fall for various thought traps, we have choices to make. Though he starts the book by saying “diagnosis is the treatment” and summarizes key points in a “Thinking Person’s Checklist,” mere awareness is not enough. Thankfully, Jacobs closes with a much more compelling call. “You have to be a certain kind of person to make this book work for you,” he says. “What is needed for the life of thinking is hope: hope of knowing more, understanding more, being more than we currently are.”

Self-awareness begins by thinking about our thinking. But it only continues with a commitment to self-transformation.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.