A Quick History of the New Year’s Resolution

Are you making a New Year's resolution this year? It's quite likely you are, as surveys conducted in recent years show that something like 40 percent of Americans make one annually. And what are they resolving?

Last year's Marist study, the annual gold standard of New Year's resolutionology, showed that their number one goal was—good news, fellow citizens!—”being a better person,” beating out the evergreen weight loss for the top spot.

The American public's endearing, if slightly loopy, resolve to be better people may lack specificity, or what the project managers in your life would call “deliverables,” but it does harken back somewhat to the original spirit of New Year's Resolution making.

While most New Year's resolutions of today are, like our modern society more broadly, typically individualistic and self-interested, the custom has more often been about affirming transcendent or pro-social values.

Planned in Babylon

New Year's resolutions have played an intermittent role in the development of Western Civilization. They appear first four thousand years ago in the annals of Mesopotamia, where the Babylonians marked their New Year (called “Akitu”—try to remember that for your pub quiz) with twelve days of religious pageantry celebrating the spring barley harvest and the greatness of Marduk, the patron god of Babylon.

A highlight of the festival came on the fourth day when the King of Babylon was paraded to Marduk's temple before the people of the city. There its high priest, dressed in the guise of the deity, would carry out a ritual humiliation, stripping his royal majesty of his official garb, slapping him twice on the face very hard, and obliging him to prostrate himself before the altar and recite a lengthy list of promises and resolutions to the god and the state for action in the coming year.

And yet, New Year's resolutions were not just a matter for the peak of Babylonian society. The common people also made promises to the gods and their fellow subjects, resolving, for instance, to pay off debts. Carrying out these resolutions faithfully would ensure the good graces of Marduk and his pals in the coming year. Breaking them could lead to a catastrophic withdrawal of divine favor. Consider that when you're contemplating letting your gym membership lapse this February.

The Roman reset

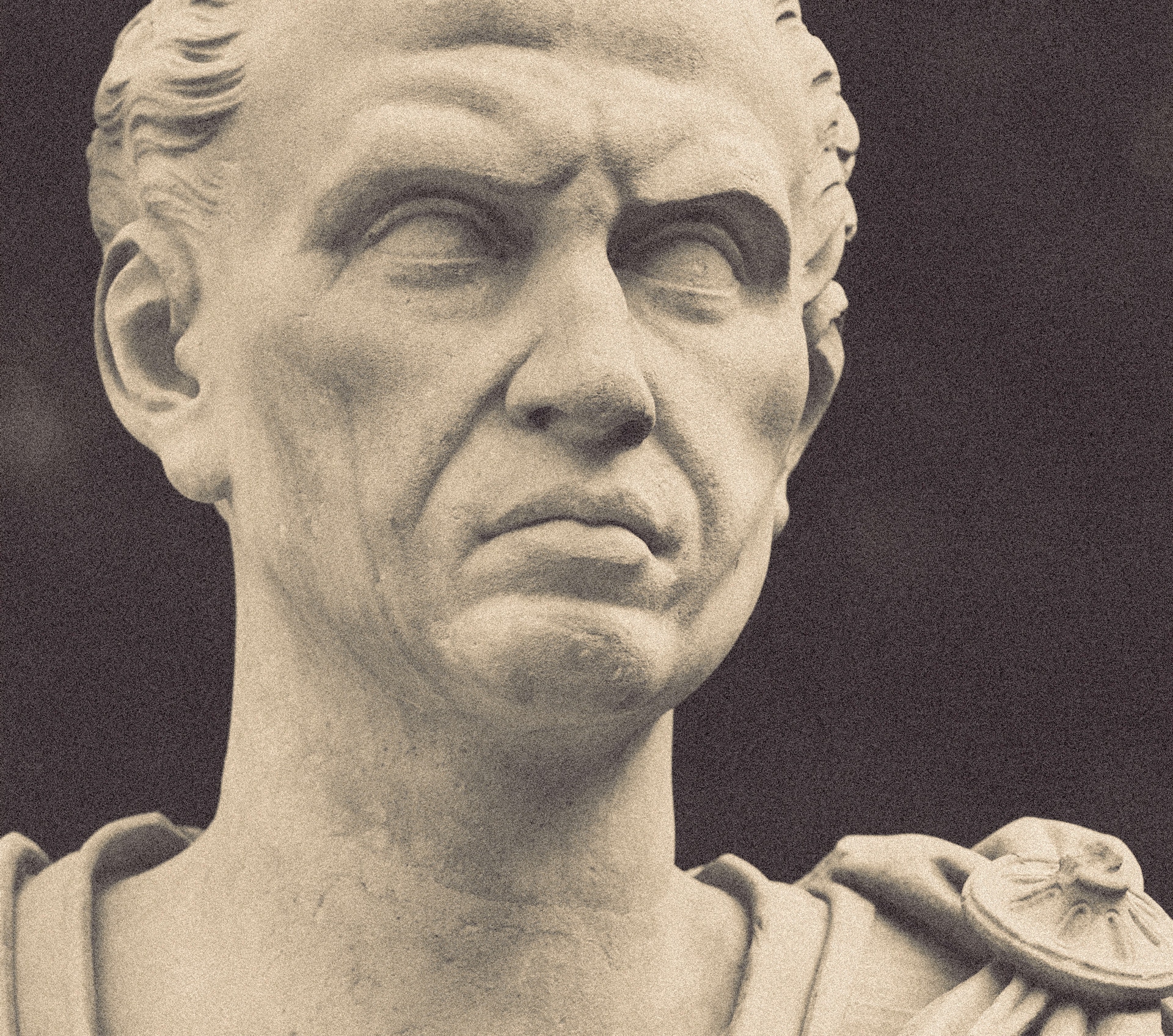

The starting of each new year on January 1 began, according to tradition, in 45 B.C., when the Roman state adopted the Julian calendar. It was named after Caesar, who commissioned it, but actually worked out by an Alexandrian Greek named Sosigenes, who can be seen portrayed by Hume Cronyn in the Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton film Cleopatra.

In fact, New Year's Day had been the first of January previously, in a tradition attributed to the mythic Roman king Numa Pompilius. Alas, from Numa's day to Caesar's the Roman calendar fell into a state of utterly bewildering disarray. The start of the New Year fell generally, but not always, in March, while lengths of months, the order of months, number of months, really everything, operated on a distressingly ad hoc basis. Eventually, nothing else would do but the sort of radical rethink you really need a proper dictator to push through.

Numa's reasoning—and Caesar's—was that the eponymous divinity of January (the two-headed Janus, god of doors, gates, and bridges, as well as beginnings, endings, and transitions of all kinds) had a logical ritual connection to the New Year. So on that day Romans would conduct special sacrifices to him and, yes, make promises of good and proper behavior in the year to come. As in Babylonia, these resolutions touched both the state and the civil society, as the start of the New Year also meant the taking of the oaths of office of that year's elected officials.

Over the period from the collapse of Rome down to the start of the modern era, the tradition of making New Year's resolutions seems to have died out, or at least down. Already in the late years of the empire, lusty pagan New Year's celebrations and vows to Janus were giving way to Christian austerity of the Feast of the Circumcision.

With the breakdown of central authority, the calendar also fell into disunity. During the Middle Ages, New Year's Day varied by country. Depending on where you lived, it might have been September 1, the winter solstice, Christmas, January 1, or the spring equinox.

Promises to peacocks

The main upholders of something like New Year's resolutions down through those centuries seem to have been the Jews, with their ten days of repentance and reflection between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. But there is at least one interesting Christian custom from the period. At the height of the Age of Chivalry, knights are supposed to have marked the New Year with the so-called Voeux du Paon, Peacock Vows, affirming their commitment to the chivalric code of conduct.

In the vivid description of Charles Dickens, “It was on the day when a solemn vow was made that the Peacock … became the great object of admiration, and whether it appeared at the banquet given on these occasions roasted or in its natural state, it always wore its full plumage, and was brought in with great pomp by a bevy of ladies, in a large vessel of gold or silver, before all the assembled chivalry.”

The peacock, said Dickens, “was presented to each in turn, and each made his vow to the bird, after which it was set upon a table to be divided amongst all present, and the skill of the carver consisted in the apportionment of a slice to everyone.”

Regrowing resolve

The modern era of New Year's resolutions seems to have begun with nonconformist Protestantism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Puritans were encouraged to lay off the ale and spend New Year's Eve in sober contemplation of the year to come, and John Wesley instituted the Watch Night or Covenant Renewal services still practiced in some Methodist churches.

The history of the tradition from that time to now, however, has been one of growing popularity and a more personal focus. Compared to the 40-something percent of Americans who make one today, only about a quarter did in the 1930s.

Are all those Americans who resolved, in lieu of weight loss or fiscal sobriety, to be “better people” last year the avant-garde of a return to the socially and spiritually unifying New Year's resolutions of the past? Time will tell. But don't get your hopes up in either case: a 2007 University of Bristol study revealed that 88 percent of New Year's resolvers failed to achieve their goal.

It's not all gloomy, though. Research has shown that announcing your resolutions to supportive friends and family and keeping them specific sharply increase your odds of success. So, if you're making a resolution this year, do as our ancestors did: add a little pomp, keep it social (and religious if that's your bent), and state your goal plainly. Michael Hyatt's just-released book, Your Best Year Ever, can help with that. Ancient Babylonians would approve.

Disclosure of Material Connection: Some of the links in the post above are “affiliate links.” This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, we will receive an affiliate commission. Regardless, we only recommend products or services we use and believe will add value to our readers. We are disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255: “Guides Concerning the Use of Endorsements and Testimonials in Advertising.